The Rub: Vianne's decision to start her business in the middle of Lent incurs the wrath of the parish priest - can she stand her ground against real authority?

The Secondary Cast:

Anouk: Vianne's six-year-old daughter. Loves her mother and the travelling, but has an imaginary friend named Pantoufle to help with the loneliness of being uprooted.

Pere Reynaud: A rigid and arrogant parish priest who sees Vianne as a threat to his community to be rooted out, no matter the cost.

Armande: An elderly town resident who recognizes Vianne as a witch and befriends her immediately.

Josephine Muscat: A troubled woman sneered at by the town and stuck in an abusive relationship - until Vianne offers her assistance.

Guillaume: A gentle old man who is greatly attached to his old dog, Charley, despite the priest's insistence that caring for a creature with no immortal soul is a waste of time.

Roux: A red-headed member of the travelling river people who set up camp in the small French town, despite the hatred and suspicion of the townsfolk.

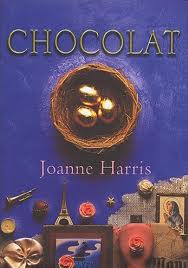

The Word: I picked this book up because, thanks to the brilliant Gentlemen and Players blowing my everlovin' mind, I've been trying to read more of Joanne Harris. So far, her books have been pleasant, mouthwatering, with lots of detail - but they never reached the agony and ecstasy I had reading her novel about the politics rife within a boy's prep school.

Vianne Rocher grew up living an itinerant existence with her mother, travelling all over the world, living different lives, working different jobs, yet still hanging on to the family tradition of magic. Vianne's mother read tarot cards, predicted the future, brewed tisanes and made good-luck charms - even as her premonitions grew increasingly dark as her own death loomed closer and closer.

Vianne was raised in a life of change and chaos, and she's lived a similar life with her now-six-year-old daughter Anouk, but the nomadic existence is starting to tire. When she and her daughter move to the tiny French village of Lasquenet and set up a chocolaterie, Vianne sees a potential place to actually settle down. However, when she runs afoul of the rigid and obsessive town priest, Vianne learns that her heritage of change and chaos might be just the thing this town needs.

The novel is told in chapters of alternating viewpoints between Vianne and her ultimate opponent, Pere Reynaud, the priest who grows increasingly unhinged by the defiance and sensuality Vianne and her chocolate shop represent. However, I wouldn't interpret Chocolat as a condemnation of the church or Catholicism - but rather the particular method this priest applies to his people.

Reynaud, who was raised in town but left for his education, holds himself above his flawed, stupid, petty flock and preaches down to them with law, theory, and rhetoric, trying to appeal to the mind. Vianne, meanwhile, is the outsider who wants to belong within the community as a part of them, and with her casual dialogues with them over a cup of chocolate, appeals to the heart and the senses with empathy and compassion. The novel demonstrates how you cannot seek to change the hearts and minds of people by holding yourself apart from them.

In this way, Vianne wins over many of the townsfolk, which prompts Reynaud, terrified of losing control over the town, to take ever-more irrational measures.

As usual, the writing and descriptions are sumptuous, and I quite enjoyed the magical realism (Vianne possesses a mild mind-reading ability which gives her insight). I've found myself comparing Joanne Harris to Alice Hoffman rather frequently (although on average I've enjoyed Hoffman's books more), and here, Chocolat reminded me very strongly of Hoffman's Practical Magic. In both, the magical element is subtle, subdued, and may or may not exist solely in the protagonist's head, but imbues both books with a spice of something special and different.

That being said, I found some elements of Chocolat to be a little unclear and haphazard (particularly the ending and some "shocking" reveals). And despite having much of her POV, I found I had trouble connecting to and understanding the motivations of Vianne.

B

The Film: *warning: book and film spoilers ahead*

It's interesting to compare the novel Chocolat to the novel Practical Magic - because I had a similar reaction when watching both of their film adaptations. Both films differed wildly (wildly) from the source material, but the films themselves were so interesting that I enjoyed both versions. In fact, *lowers voice to a whisper* I may have enjoyed the film Chocolat more than the book.

Is it a faithful film adaptation? Oh Hell no. They add stuff, they change stuff. Most of the characters only bear mild resemblances to their literary counterparts - although Josephine Muscat (Lena Olin) remains startlingly faithful to the original.

But is it an enjoyable movie - and does it have a good story on its own? Yes and yes. I could detail all the stuff they change from the book, but then this list would go on forever. Instead, I will speak about the three main differences and how they affected the story and my reaction to the film.

1. Vianne's Origins.

In the novel, there is no real specific reason for why Vianne and her mother, and consequently Vianne and Anouk, keep moving around from town to town and changing their identities. The implication is that it's because Vianne and her mother are witches, as well as an ingrained fear on her mother's part that staying too long in one place will allow "The Black Man" (an archetypal symbol of the church and the authorities) to take Vianne away. We later learn in an almost throw-away scene that Vianne's mother may have actually snatched an infant Vianne from another woman's pram, which gives a wholly different context to their frantic travels.

In the film, Vianne reveals she's the daughter of a French pharmacist and a South American woman who belonged to a tribe of wanderers duty-bound to follow the summons of the north wind and dispense sacred cocoa-themed remedies from town to town. Vianne grew up following the wind and learning the ways of chocolate from her mother, but has trouble continuing that tradition with her lonely, sullen daughter.

To me, I liked this element. Aside from the chocolate-flavoured-Mary-Poppins vibe, I loved the romanticism and magical realism of this backstory as well as how cleverly, effectively, and efficiently it explained Vianne's motivations, intentions, and the importance of chocolate in her life.

2. The Time Period.

In the novel, the story is set in more or less modern times, early nineties at the earliest. The town of Lasquenet is just such a small, out-of-the-way backwater that it still maintains an old-fashioned, timeless quality. Vianne, who's travelled all over the world, is depicted as a force of modernity in a forgotten town that somehow missed 60 years of social development.

In the film, the story is explicitly set sometime in the late 1950s-early 1960s. The townsfolk are still very much affected by both the world wars and Elvis music is filtering in very slowly (thanks to the town's adorable baby-faced parish priest). I love period pieces so I enjoyed this.

As to why the filmmakers decided to take a modern novel and make it a period piece, I suspect it might involve the suspension of disbelief. Modern audiences (particularly North American ones) might have had trouble believing a modern town would still remain so conservatively religious and socially antiquated that they needed Chocolate Mary Poppins to remind them that breaking Lent isn't the end of the world and that beating your wife is Wrong.

Do I believe there are still towns in Europe and North America that actually are still like that? Definitely, but moviegoers as a whole tend to watch films with an idealistic and naive bent and want to believe that modern society is no longer like this - therefore, it's more comforting to encounter this type of story in an historical setting where the time period can explain it away.

3. The Antagonist.

In the novel, Vianne is opposed in all things by Pere Reynaud, a controlling, arrogant, contemptuous and theologically-rigid priest. It's not just the notion of serving chocolate during Lent that offends him, or that by doing this Vianne weakens Pere Reynaud's iron-clad moral control over the town. Vianne's very presence is the ultimate threat because it's distracting and colourful and indecent and sensuous - Pere Reynaud thrives on control, and Vianne threatens his control over himself. That's not to say Pere Reynaud is a cartoon, but from his POV we can clearly see he is a megalomaniac whose lust for power is so heavily swaddled in religious rhetoric that even he doesn't recognize it. As the novel progresses and he loses more ground, he eventually descends into complete insanity.

In the film, the filmmakers decided to sidestep possible religious controversy by rewriting Vianne's antagonist as the Comte de Reynaud, the town mayor (played by Alfred Molina, one of my favourite actors). In the film, the Comte is very much an antagonist rather than a villain, and a far more sympathetic figure. While he is still arrogant and a bully (the brand-new baby-faced priest is so terrified of him that he lets the Comte "revise" all of his homilies beforehand), his good intentions and his attempts to lead by example are more evident. He genuinely cares about his town and its people but he bitterly resents Vianne's usurpation of his role as authority figure.

Pere Reynaud and the Comte share very little in common, character-wise, beyond a desire for denial - not only of the corporeal pleasures for Lent, but of the truths that are too painful to accept (the Comte hides his heartbreak over his wife leaving him by telling people she is merely "vacationing" in Italy, and Pere Reynaud glosses over the teenage trauma of discovering his mother in flagrante delicto with the parish priest who was his religious mentor).

There is actually one major scene that both antagonists share - in the novel, when Vianne decides to hold a chocolate festival on Easter, an enraged Pere Reynaud finally snaps and breaks into her shop to sabotage her work. After weeks of futile self-denial, Pere Reynaud has a complete mental breakdown at the sight of so much delicious food and he gorges himself, completely abandoning his evil plan, his dignity, and his Lenten fast to shove sweets into his face instead - only to be humiliatingly woken up by his parishioners the next morning, covered in melted chocolate.

However, because of the different ways these antagonists were developed, this scene has a different context in the film. In the novel, Pere Reynaud's breakdown is Vianne's ultimate triumph, it's a glorious chocolate-coated scene of Schadenfreude as he gets his just desserts in the most delightfully literal and public way possible, after which he flees into the night, never to return.

In the film, this scene comes across as tragicomic and sympathetic, a proud man finally admitting to weakness. He's spent the entire film believing he can control, change and better everything if he just believes and works hard enough - only to discover he's just as human and fallible as his townsfolk.

In the novel, Harris uses pig imagery to describe Reynaud's breakdown - he squeals and keens as he eats the chocolate. The breakdown in the novel turns Reynaud into an animal, to be laughed at and hated. The breakdown in the film makes the Comte de Reynaud seem more human - to be sympathized with and forgiven. The Comte is actually saved from public humiliation by the quick thinking of Vianne and the parish priest, who finally gets to give a stirring Easter homily in his own words, and a grateful Comte befriends Vianne.

I actually loved the film's antagonist way more than the incredibly creepy Pere Reynaud. Yes, I'm a sucker for Alfred Molina, and even more of a sucker for redeemed-antagonist storylines.

Yes, I still liked the novel, and acknowledge that the film changed a great deal of the storyline. However, from a purely objective perspective - I enjoyed the film's story more than the novel's.

Thanks for that review, I've been eyeing the book for quite some time now, since I saw, and fell in love with, the movie (and Juliet Binoche - isn't she simply fabulous?), but I guess I put that on the back burner and get Practical Magic instead, seeing how Hoffman is another author I always wanted to give a try.

ReplyDeleteGreat comparison. I love the movie but haven't read the book - from what you've described, I think the movie does sound better, but I still want to try the book one day and compare for myself.

ReplyDeletegreat comparison! Really highlights the differences between the book and the film, which I hadn't really noted in depth before reading this

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteThanks for sharing! I've been faithfully watching the movie Chocolat every Lent/Easter for several years. This year I used a Lenten guidebook, Chocolate for Lent by Hillary Brand, which has the movie Chocolat as its text, and I also read the novel. Now I'm reading the novel's sequel, The Girl with No Shadow. I agree with your observation of the different impacts of the novel and movie Chocolat. I, too, prefer how the antagonist was redeemed, rather than ridiculed, in the movie. I see Chocolat as an exploration of Law vs. Love, Conformity vs. Transformation, Control vs. Freedom. As I deal with the Vianne Rocher novels, I also get reminded of the Harry Potter books and of Robert Cormier's The Chocolate War.

ReplyDeleteI am watching the movie again I’ve seen it a lot and we share a love of authors as I love Practical Magic also. This book changed my life. Books can change lives that’s why they try to silence them.

ReplyDelete